Recently, I became hooked on a video game for the first time since I was a teenager in the early days of home computers. While my children checked Instagram in the evenings, I would fire up Star Wars: Galaxy of Heroes on my phone. After my wife began to tease me for becoming as much a phone slave as the kids, I began to think about why this game interested me so much. And then it hit me, it’s the digital equivalent of my major collecting interest: vintage Star Wars toys.

I’ve collected Star Wars figures since the late 1970s, when I could actually achieve the collector’s ideal: owning a complete set of all the figures in existence. The toy industry quickly moved such aspirations far, far beyond my financial means, but I never fully gave up collecting Star Wars figures even as other interests and obsessions came and went. Today, I have an attic full of vintage Star Wars toys, but they only ever come out a couple of times a year. (As I’m also a book collector and writer, and have worked in the book industry for almost 20 years, the shelf space must go to the book collection, which is very much a working library.) The game I got hooked on is essentially those 4-inch plastic figures come to life. You assemble squads and embark on missions, fighting against the Empire — essentially a continuation of the battles I acted out with my figures in childhood. But what’s so addicting is collecting the characters. You get a handful at the start, and must unlock others through game play. So, it’s the perfect game for a life-long Star Wars collector.

These musings started me looking for information and books about the psychology of collecting, and I learned many interesting things.

The Impulse to Collect

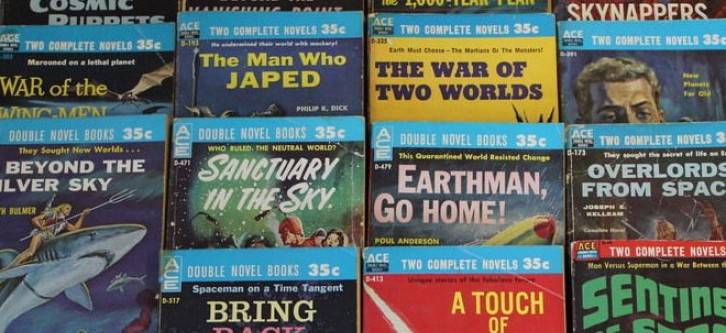

The consensus seems to be that we collect for one of two primary reasons: logical or emotional. We might focus on signed, first editions of 1920’s American fiction because we believe the demand is strong, the writers famous, and their value likely to increase over time — that would be a logical rational for collecting. Or, we might collect pulp, golden-age sci-fi paperbacks because they remind us of when we first discovered the genre as a teen in the 1950s; that would be primarily an emotional rationale.

After one or the other of those major impulses gets the ball rolling, we all derive different things from our collecting. Or, to put it in slightly more clinical terms, our motivations to continue collecting come from a small set of factors which vary from collector to collector.

Motivating Factors

Individual motivating factors can include the accumulation of knowledge (at one end might be the desire to read all of Dorothy Parker's work, at the other might be the aim to become the expert on Parker’s printed work in all formats), the quest for pleasure or relaxation (safe in the knowledge that you will always have great reading-matter at hand), or the altruistic impulse to preserve an area that you deem worthy of study (whether or not you plan to share your collection with the public). This critical impulse may impel the collector in a number of other directions: the desire to prove that something is an important area, the desire to exhibit your expertise, or even the aim of building up a museum-quality collection that you (or your heirs) could either donate or sell to an important library.

It’s important to understand our own motivations for collecting. For one thing, it can help us focus our interests and purchasing.

When I was in college, I wrote my thesis on Salman Rushdie and intended to pursue a doctorate in his work. I eventually chose a different career path, but still collect Rushdie’s work. My interest is academic and literary, so I focus on obtaining and reading all of his work, as well as his major influences and books about his work. While I have a few signed first editions, I don’t aim to track down pristine first printings of every edition of his books. Although I do have some interesting ephemera, playbills from adaptations of his novels, programs from his speaking events, etc. For my Star Wars collecting, I aspire to own one of everything, but not the most pristine or perfect examples of each. (There’s a tendency among Star Wars collectors to prize unopened boxes and pristine packaging above the toy itself. I don’t go there. What’s the point of a toy collection that can’t be played with?) The factors driving my Rushdie collection are primarily logical (academic interest, completist tendencies, and the desire to enjoy his work whenever I wish), the factors driving my Star Wars collecting are largely emotional (the toys remind me of the carefree days of childhood and it’s a lot of fun to dive back into the world of the Star Wars mythos now and then).

Once we have zeroed in on an area to collect, there are many different directions our motivations may take us:

Competition — The desire to own the most.

Aesthetic — The desire to own the most beautiful examples.

Social — Is this a collection we can showcase to others?

Glory — Do we want to be known as an expert or great collector?

Altruism — Is the collection for ourselves, or do we harbor the goal of donating it to an archive at some point?

Nostalgia — Is the collection something that arouses warm feelings and happy memories?

Control — Is the area in danger of being lost or in scarce supply? Will our collecting this area save it for posterity?

This list is not exhaustive, nor are the motivating factors mutually exclusive. We can enjoy the warm fuzzies of nostalgia and still harbor the hope of building up a collection that a museum would be glad to acquire.

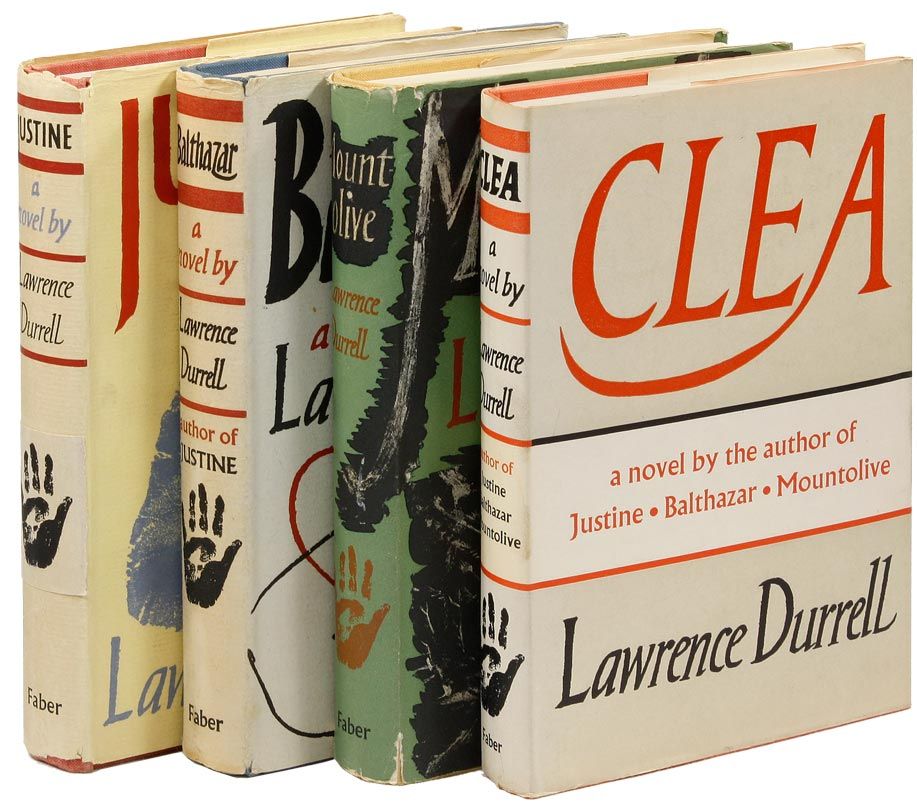

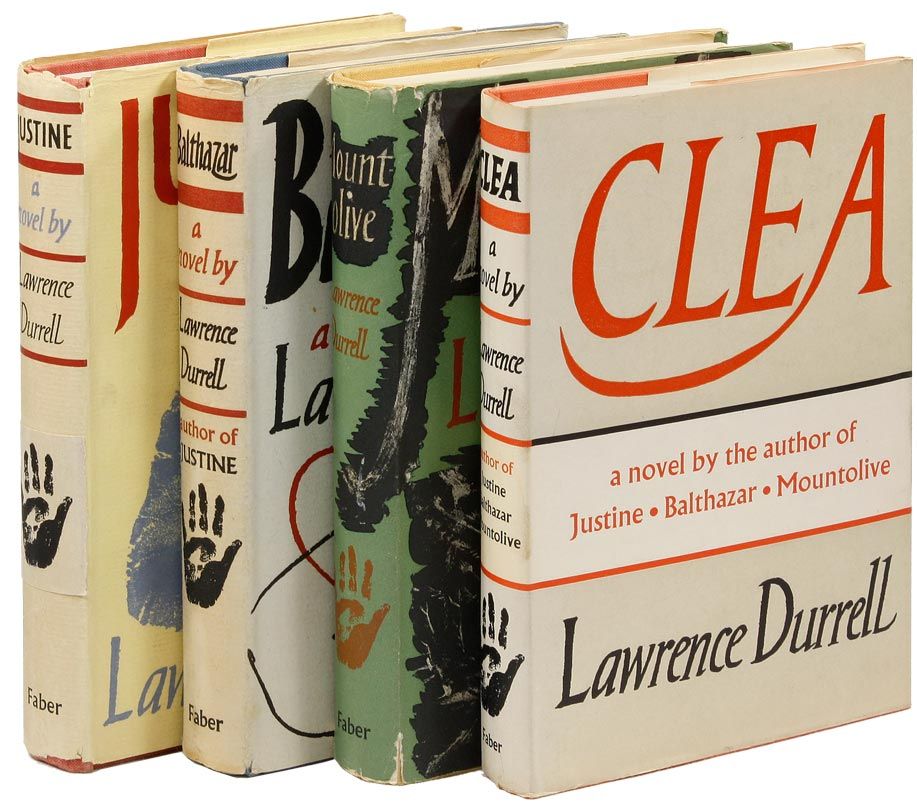

The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell

London: Faber & Faber, 1957-60. First Edition. Durrell's magnum opus, chronicling the lives of British expatriates in Egypt before WWII. The tetralogy was selected as No. 70 on The Modern Library's list of The 100 Greatest Novels of the 20th Century. Four octavo volumes. Cloth boards; dustjackets; 253+250+320+287pp. First Printings. Each Near Fine, clean and unmarked in original dustwrappers. (Offered by Lorne Bair Rare Books)

Another factor governing the collecting impulse is often a desire to chart your own course. Perhaps you feel an author is under-appreciated or an unpopular genre is worthy of preservation. Sometimes the non-initiated may not appreciate something until you showcase the collection in all its glory. One bookplate may seem unimpressive by itself, but a collection of hundreds organized by decade may reveal great art, clever wordplay, or interesting conventions of design. One vintage postcard may not seem like much, but a collection of hundreds from a particular resort or destination may reveal the multi-ethnic face of a region, highlight changing fashions, or give visual form to a city’s changing fortunes.

Sometimes, one book can slowly spur a collection. I’m a huge Lawrence Durrell fan — although it was his brother Gerald’s memoirs that introduced me —and reading the Durrell brothers and learning about their pre-war Greece has slowly drawn me to many other peripatetic writers of the inter-war years, such as Patrick Leigh Fermor and Joseph Roth. I don’t consider myself a collector of Durrell’s work, but I am slowly trying to read it in its entirely.

Collecting Versus Hoarding

Most psychologists delving into the collector’s mindset explore the line between collecting and hoarding. Most conclude hoarding is simply compulsive acquisition or acquiring for acquiring’s sake. Which is why it’s important for collectors to understand our short- and long-term motivations. (I realized long ago that most Star Wars memorabilia is simply overpriced kitsch, which is why I focus primarily on 4-inch figures.)

Having a goal or an over-riding framework in mind can help guide purchases, and save you from potentially expensive impulse buys that might not add to the overall collection in a meaningful way. It can also help you work with ABAA members, who will be keen to know if you’re looking for a reading-quality copy of a hard-to-find novel to complete your collection, or if only a signed, Fine, and preferably association copy will do.

After a few weeks of addiction to my new computer game, I began to realize the gameplay was repetitive and becoming stale, the fun was in collecting new characters and unlocking their abilities. As usual, another one of my past-times becomes just another excuse to collect things.

I know that my Rushdie collection will simply amount to an additional few boxes of books for my heirs to dispose of — unless some of them come to appreciate his work; but perhaps my Star Wars collection will become part of my children’s nostalgic memories and may in turn be passed along to their offspring, or maybe it’ll be sold off as a nest-egg for them to use in pursuit of their own interests? Who knows? Either way, both collections will have given me years of pleasure and education, even if they also inspire me to waste the odd evening playing a video game.