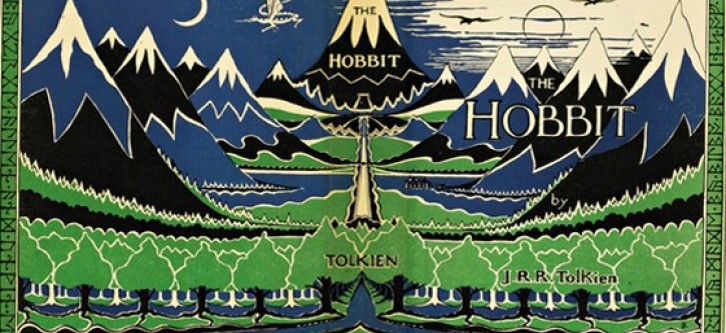

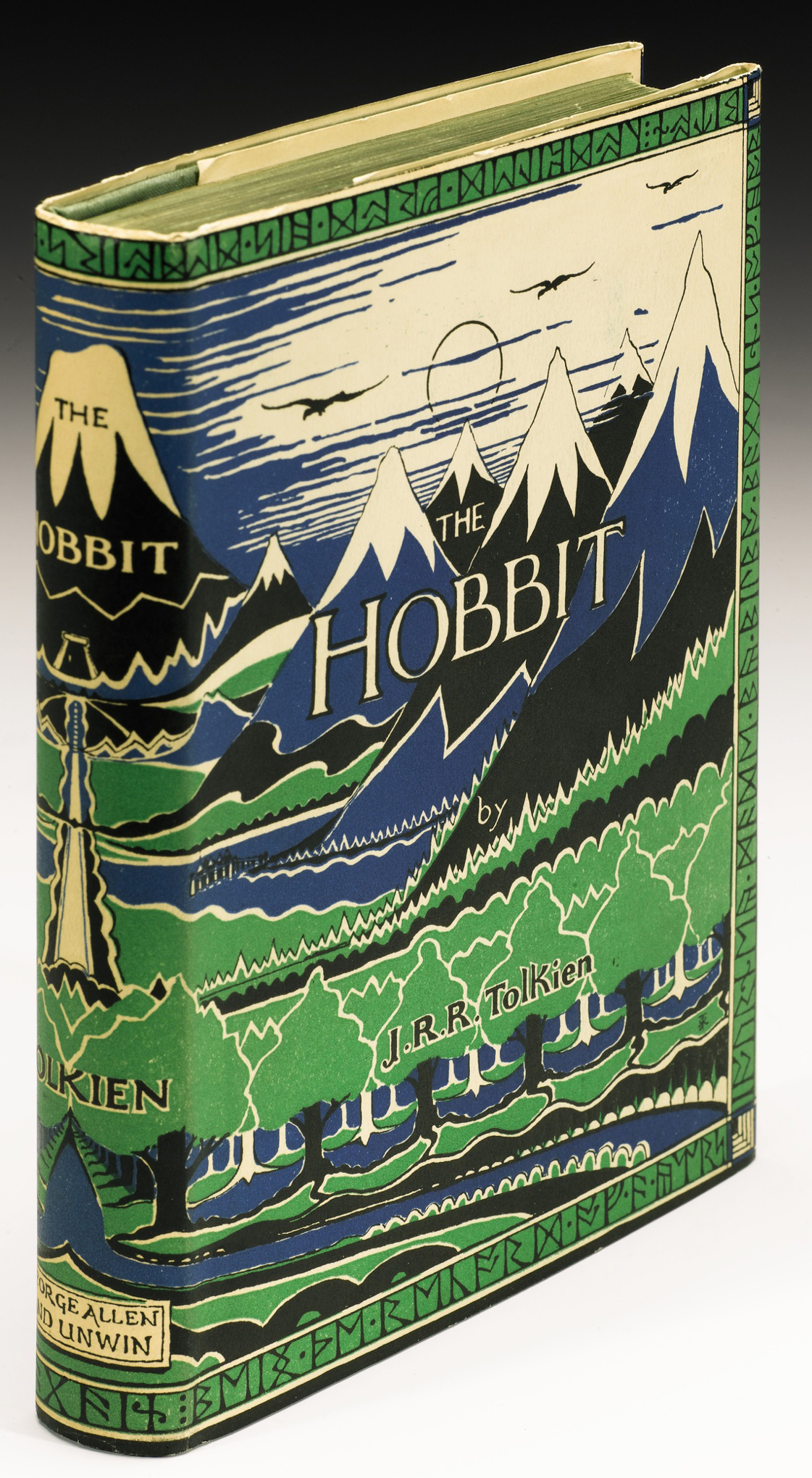

National newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic were abuzz over the weekend with the news that a first edition of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit had sold for a record price at auction. The book sold for £137,000 (about $210,500). To put this in perspective, the previous record price was £50,000.

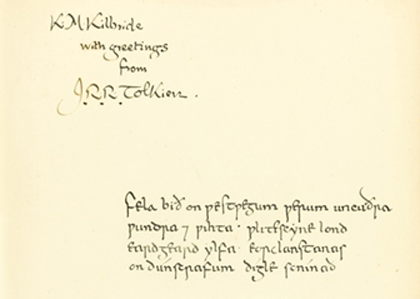

Why did this sale outperform expectations so astonishingly? Well, it might have had something to do with the fact that this was one of the most-sought-after of all signed books, a presentation copy, given by Professor Tolkien to one of his students, Katherine Kilbride. Tolkien did not inscribe many presentation copies, so the book is certainly rare. Not only that, but he added an inscription in Middle English.

The "Kilbride Hobbit" (Image source: Sothebys)

ABAA-member Mark Hime of Biblioctopus in Century City, CA has intimate knowledge of this particular copy, having sold it twice in past decades.

Hime commented to another bookseller, Brad Johnson of The Book Shop in Covina, CA, that “to my knowledge, the presentation copy of the Hobbit to Kilbride, was the first 20th century novel ever priced or sold for five figures -- though Margie Cohn had a set of the three Ulysses priced $10,000 in her catalog about a year earlier.”

When we contacted him for any further thoughts on the sale, he had this to say:

"I was answering Mr. Johnson's question about that copy's appearance for sale at $12,500 in a 1980 Biblioctopus catalog. The key phrase in the quotation is ‘to my knowledge.’ Institutional memory, in its meaning as information about a company's past, is always a mercurial thing. That said, in 1980 I had not seen a 20th century novel cataloged by a bookseller for $10,000 or more, and I intentionally priced this one to do just that."

I sold the book in 1980, and actually got it back a few years later, and sold it again for more, though I do not remember how much more."

Asked if the spectacular price indicated anything about the general state of the rare book market or the influence of the popular movie versions of Tolkien's novels on prices, Hime had plenty to say:

"There is no general anything in book prices. Observations can be made about one or another wedge of the book market, but it is an inefficient market, so the veracities of generalisms are usually crushed under the weight of their exceptions. That said, there was a huge, and largely justified, spike in the prices obtained for 20th century fiction between 1975 and 1995, and Tolkien rode that wave. Since then, prices have continued to rise for those titles, and particularly those copies of those titles, that the marketplace has deemed to remain in high demand, but there is an ongoing adjustment in real values (as opposed to bookseller's delusions) for titles for which there is diminishing demand, and particularly for average copies of them (when one sees 20, or even 5, comparable copies of a novel on the net for sale, that book is not scarce and is almost surely overpriced, and bookseller stubbornness will not change reality as they watch these mediocrities back up in their inventory like bad plumbing). In the old days, a book was called scarce when a specialist in that book saw a copy once a year, and called rare when said specialist saw a copy once every 10 years. Apply that standard to today's net and one can see that the terms scarce and rare are abused, even by competent booksellers. One insight that might be called worthy is that in the case of many 20th century novels, there are 25 very good copies for sale and zero fine copies (although standards of condition have collapsed, and misuse of terms is widely seen, so a book called fine may look like it has been microwaved for 10 minutes with a tomato). This disparity of fine copies to very good ones suggests that fine copies, when seen, are often priced double or triple what very good copies are priced when they are, in fact, 30 times as scarce. This is another aspect of an inefficient market and the savvy collector knows that if they can buy a book that is 30 times as rare for 3 times the price, the value (bargain) is obvious. This rant barely touches the subject of prices, but it is an introduction, that should encourage any person interested in books to take a deep breath, feel their feet, and rethink the matter in the serene and lucid interval between actions.”

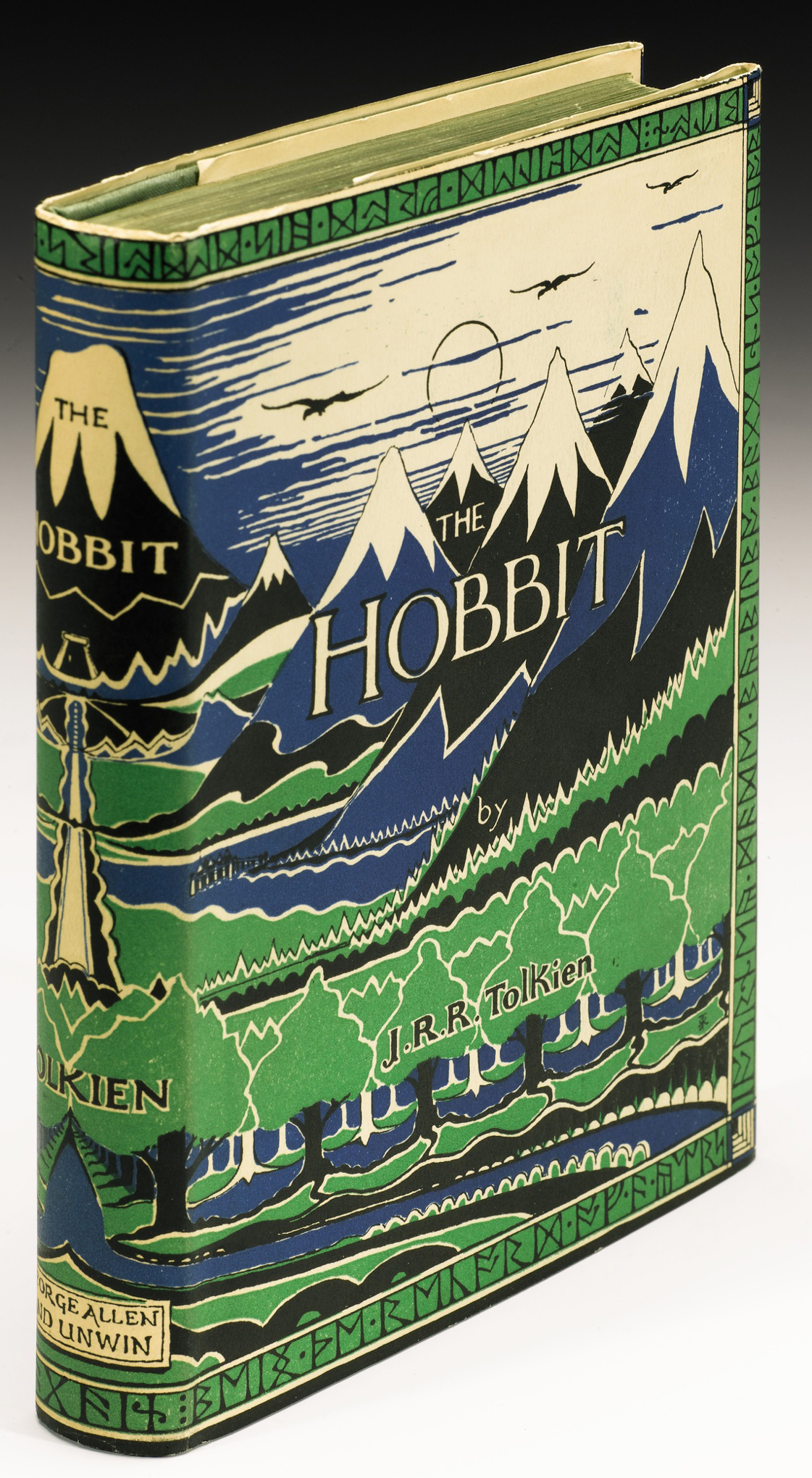

The Sotheby's catalog identified the inscription as being in Elvish, the language Tolkien invented for Middle Earth. But, Hime pours cold water on this claim:

"The inscription to Kilbride is in middle–English (which has nothing to do with Elvish) and translates as:

‘In the West there are many wonders and creatures unknown to men. (There is) a beautiful land, a dwelling of elves; (There) precious stones shine secretly in mountain caves.’”

Which is a good reminder not to believe everything you read in an auction catalog.

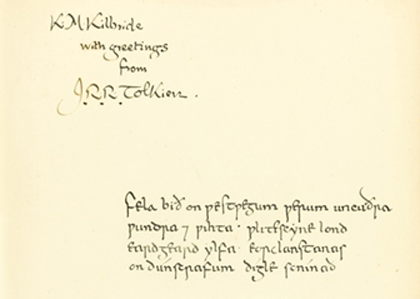

The inscription from J.R.R. Tolkien to Katherine Kilbride. Elvish or Middle-English? You be the judge... (Image source: Sothebys)

The Guardian supplied some background information on Kilbride, one of Tolkien's first students, with whom he corresponded for years:

"Kilbride, who died in 1966, was “an invalid all her life”, according to her nephew, “and was much cheered by (Tolkien’s) chatty letters and cards ... books were given to her as they were published”.

In a letter thanking Tolkien, now kept in Oxford’s Bodleian library, Kilbride tells the author: “What fun you must have had drawing out the maps.”

So, while this sale indicates that collector interest in rare books at the high end of the market remains strong, I wouldn't get your hopes up about your old Tolkien hardcovers -- unless that is, you hapen to have another of the very few presentation copies.

Editor's Note: Mark Hime sent us this follow-up note about the article above.

"I am doubtful that your article prioritizes the forces behind the price of The Hobbit correctly. It was not "provenance, provenance provenance.” The price was driven (in this case) by the usual combination of factors. Condition (fine book and superb unrepared dustjacket) and the quality of the inscription (long, contemporary with publication, interesting because it is in middle–English, and beauty because it is in his fine calligraphy, and peculiar looking). The same inscription to someone else would have been just as appealing. In fact, the same inscription to someone closer to Tolkien (one of his children, his wife, the publisher) would have had even greater provenance. However the copies inscribed to those people, that have been seen, did not have the other elements of this inscription. And closeness of the recipient to Tolkien is not in itself the ideal. One could rightly imagine that a celebrity inscription, even one dated much later (not contemporary with publication) to someone famous even though Tolkien had met them only once (say Winston Churchill, or Marilyn Monroe, or Albert Einstein) would have generated even wider interest, and in this case the rhetoric of “provenance, provence, provence” would have been closer to the truth.

Mr. Rennicks is due all praise for seeking something to write about with potential interest to a larger audience than the usual articles from ABAA sources."

Search abaa.org for copies of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien...

Search abaa.org for copies of The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien...