Millions of people who have joined, or watched, the recent protests across the country, beginning with the March for Women, have been struck by the diversity of signs in the crowd. Princess Leia as political crusader, puns riffing on the latest social media meme, diagrams of ovaries, statements of solidarity with Muslim refugees – all have been present, in endless variety. Surprisingly, perhaps, it was not always so. Many libraries and museums collect historical protest signs, and the study of these signs reveals many changes over the years — not only in the issues directly addressed by the signs themselves, but in evolving styles of communication, and the influence of the broader cultural environment.

It might seem surprising that some libraries, committed to the preservation of literature and the written word, also collect protest signs. If the effort of prose is to persuade, then such signs (as well as pin-back buttons and bumper stickers) are the epitome of concise communication. The simplest signs simply state an opinion, while others make more of an effort to change the reader’s mind, to use a turn of phrase to catch attention (and converts). And some signs – often those that reveal the most about their society – make more complex use of text and image, playing the part of a hand-held, sturdier version of a propaganda poster.

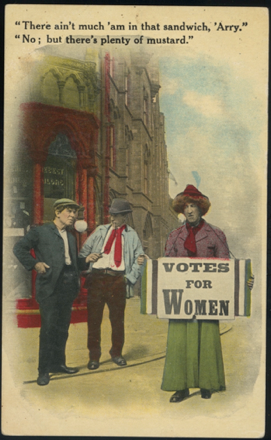

We could trace the origins of hand-carried political signs to the Roman era if not earlier, but for the purposes of this blog we will examine causes that are more familiar to the modern reader. If we begin with the social movements of the early twentieth century, such as Prohibition and the Women’s Suffrage movement, early protest signs were textual and very simple. The slogan “Votes for Women” conveyed a frank demand; the presence of women (and men) marching with a line of such signs was intended to convey the breadth of support for this position in society. Sometimes groups of suffrage activists would promote a major rally by walking in line with signs naming a venue and time, as with this 1920 demonstration in Brooklyn announcing a visit by Emmeline Pankhurst.

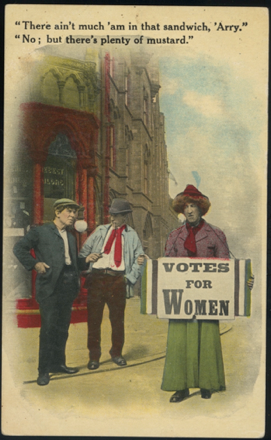

This misogynistic postcard published by Bamforth’s Comics, postmarked 1914, mocks suffrage activists and their “sandwich board” signs. (Photo courtesy of Bolerium Books)

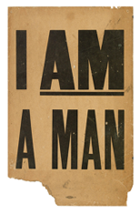

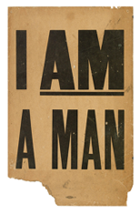

The standardization of signs was seen as vital to “branding” a demonstration and communicating its message clearly. Sometimes signs were printed in large quantities with plain, direct slogans to maximize media coverage. One of the most memorable such signs, at the intersection of the Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, was the simple statement “I AM A MAN,” used by striking Memphis sanitation workers in 1968.

This sign condenses the essence of a movement down to four short words – the ultimate statement of dignity in the face of oppression. When Martin Luther King Jr. went to Memphis to show support for these striking workers, he was assassinated. So freighted with emotional power is this legacy, that when a damaged example of this sign appeared at a Swann Galleries auction in 2016, consigned by the daughter of the man who had originally carried it, it sold for $23,750 on an estimate of $6-9,000.

This sign condenses the essence of a movement down to four short words – the ultimate statement of dignity in the face of oppression. When Martin Luther King Jr. went to Memphis to show support for these striking workers, he was assassinated. So freighted with emotional power is this legacy, that when a damaged example of this sign appeared at a Swann Galleries auction in 2016, consigned by the daughter of the man who had originally carried it, it sold for $23,750 on an estimate of $6-9,000.

Though mass-printed at the time, most of these signs were damaged or destroyed through the process of being used exactly as intended. Those that survive command substantial prices because they have become iconic with the passage of time.

At many demonstrations, pre-printed signs or signs painted by volunteers would be prepared beforehand and distributed to attendees as they arrived. Guides to sign-making often emphasized consistency of message, as well as etiquette. Used signs should be gathered together for potential re-use in the future; in no case should used signs be abandoned at the site of the demonstration, for the sight of such a mess would sully the cause in the eyes of onlookers.

Signs that were hand-painted were still often produced by experienced sign-painters in uniform style. These painters produced expertly laid-out signs, using slogans that had been settled upon by the organizers of the demonstration. The signs held in this 1946 anti-lynching demonstration at the White House exemplify such hand-painted work.

Postcard by Helaine Victoria Press, 1989, using photo from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

By the latter half of the 1960s, signs became more diverse, and the freewheeling artistic spirit of the hippie movement changed sign-making. The organizers of structured demonstrations still sought to hone the message that was being projected, but the larger the rally, the more individual interpretations one might encounter, sometimes to the dismay of organizers. With the broadening of the anti-war movement into student and religious communities, the resources of college print shops, art instructors, and even church printers went into the production of signage. The colors, floral motifs and peace signs of the Vietnam era continue to reverberate in signs of today.

(Photograph courtesy of Elise Liu)

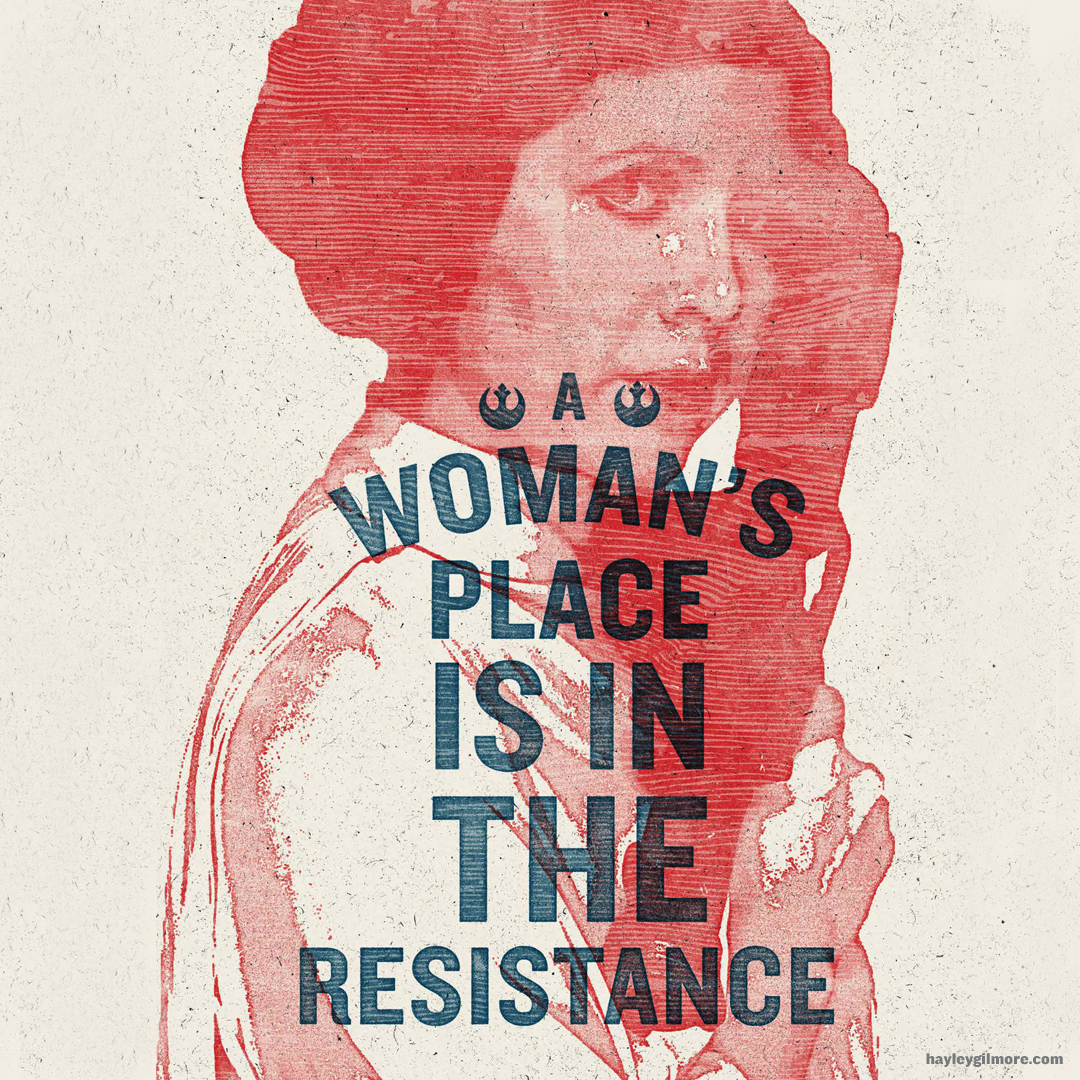

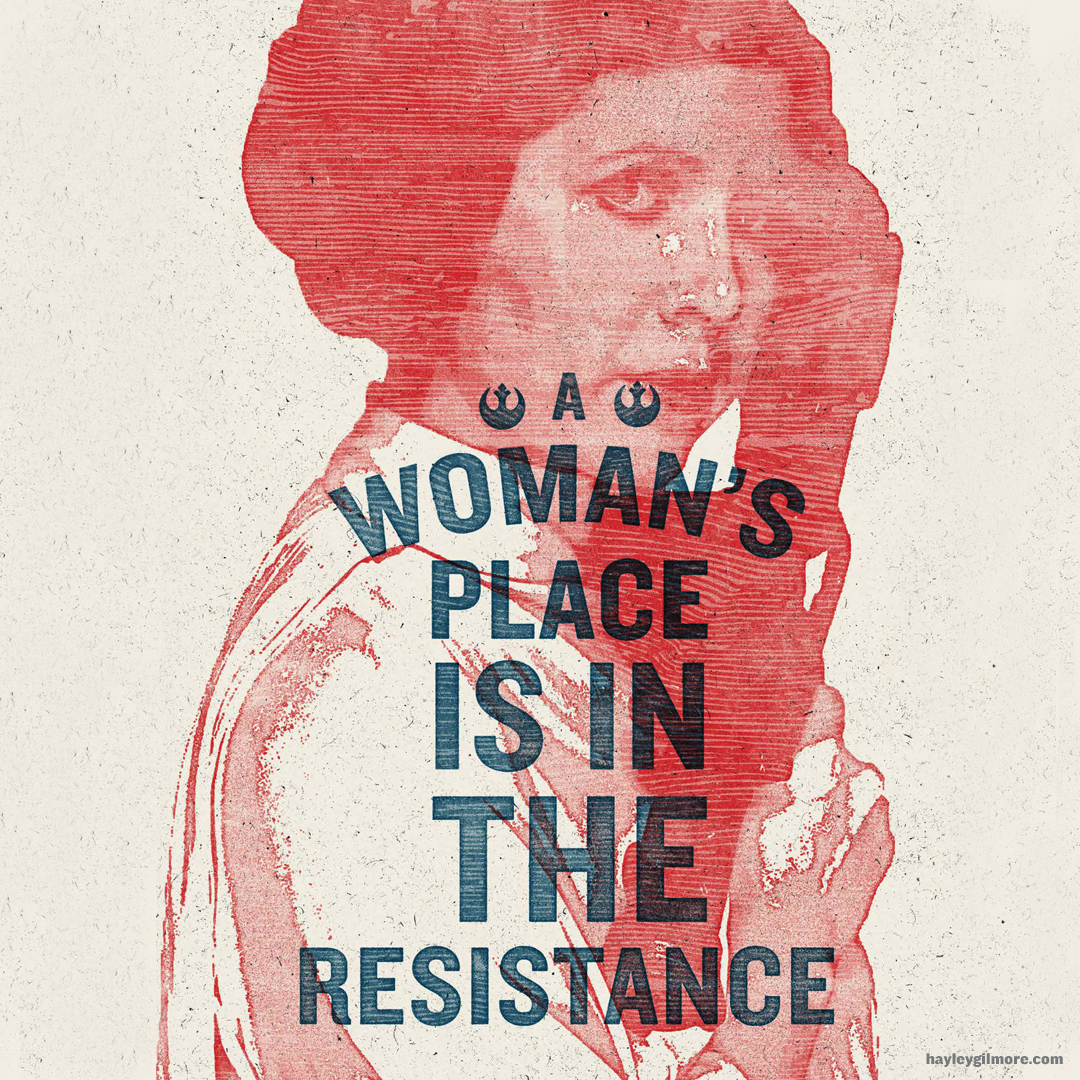

Many local organizations and movements invested in equipment for making simple silkscreened designs, so that posters, signs and leaflets could all be produced with a consistent motif. Today, graphics software and home computer printers make it possible to create extraordinarily complicated designs that can also be repeated to the point of ubiquity. Several Facebook memes featuring Princess Leia of Star Wars appeared as signs all over the country during the Women’s March in January.

(Image: Hayley Gilmore)

The poster above was spotted at rallies everywhere after having been shared on social media. The poster below shows a more individual take on a similar theme.

Groups including the Amplifier Foundation posted designs online that could be freely printed for use during the rallies. One of the most ubiquitous of these was created by Shepard Fairey, designer of Obama's 2008 "Hope" campaign poster.

The group effort of preparing signs before a demonstration is a cultural phenomenon that has endured through all of these changes. Most of these signs, even with individualized designs, are created in the company of friends or fellow activists. Whether volunteers are gathering to assemble pre-printed signs, or spreading out their supplies to paint totally new designs, the camaraderie of working together brings the “social” into social movements. My own memories of painting signs with Korean students at UCLA, or with a group of guys from Zimbabwe who were playing Bob Markey cassettes on a boom box, are unforgettable moments from my teenage years.

The boom in sign-making this year has been dramatic enough to affect sales figures for the raw materials. According to the New York Times, the sale of poster boards increased by 33 percent in the week before the Women’s March, and foam board sales increased by 42 percent compared to the same week in 2016. The New York Times reports that “More than 6.5 million poster boards were sold in January, with nearly one-third sold during the week of the march. Sales of easel pads and flip charts grew by 28 percent… Specialty markers were up by 24 percent; permanent markers, 12 percent; glue, 27 percent; and scissors, 6 percent.”

Soon after the Women’s Marches, Washington DC hosted the March for Life, an annual rally by opponents of abortion. Photos from the event show that protest signage is not exclusively a “radical leftist” phenomenon. Thousands of signs were pre-printed for distribution, so the organizers succeeded at exerting greater control over messaging, a flashback to more traditional usage of signs at rallies to make a specific argument. The organizers also emphasized sign etiquette in a way that used to be more common on the left, with instructions on the website stating “Do not leave trash or signs on the grounds of the National Mall, Supreme Court, or Capitol. This is our Nation’s Capital and we should treat it with dignity and respect. If trash bins are full, please carry your trash or sign with you until you find an available trash bin.”

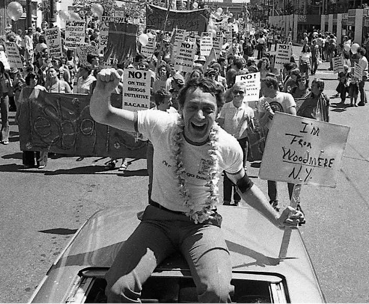

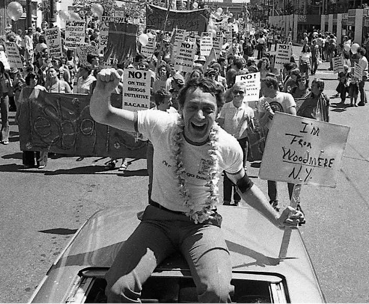

The signs one sees at a rally are not always approved by the organizers. In 1978, the Gay Freedom Day parade in San Francisco was run by a non-profit that wanted to steer clear of any political advocacy. John Durham (now of Bolerium Books) was part of a group, the Bay Area Coalition Against the Briggs Initiative (BACABI), that opposed a ballot measure that would have banned gay teachers in California. Harvey Milk was part of a different group that also opposed the Briggs Initiative. When Milk was chosen to lead the 1978, BACABI decided to flood the parade with pre-printed signs from their organization, flouting the ban on political advocacy. Durham and others brought large numbers of pre-made signs to the parade to distribute. One widely disseminated photo of Harvey Milk at the parade has a forest of these BACABI signs in the background.

For a library or other institution that seeks to preserve historic protest signage, there are many factors that determine the “importance” of a sign, and institutions will weigh these factors differently depending on their priorities. For example, is it more important to showcase iconic designs, those standardized images that defined a movement, or signs that are more unique illustrations of individual creativity? Does the institution seek to preserve the physical signs themselves, or to preserve their images in a digital file? Here in San Francisco, the Public Library decided that the endless diversity of signs at the Women’s March and the space required to store them made it unfeasible to archive the signs themselves, but it has systematically collected digital photographs. The Sutro Library at SF State University, in contrast, has collected physical signs.

Mattie Taormina, Director of the Sutro Library, with a new donation – a sign used at San Francisco International Airport on the evening after the announcement of travel restrictions on visitors from seven Muslim countries.

Several universities and public libraries made a concerted effort to collect examples of the handmade signs used at the Women’s March (for some media coverage, see the links below). At least one ABAA bookseller got involved as well, Johnson Rare Books & Archives in Covina, CA, where signs collected on behalf of the University of Southern California are shown here being displayed in the window.

The libraries and museums that collect protest signs see them as more than a handful of words on poster board. They reflect broader social currents, sometimes highlighting their most personal implications for the sign-maker. Which of today’s placards will be recognized as iconic half a century from now?

Media coverage of the institutional collection of signs:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2017/01/22/professors-stash-rally-signs-preserve-piece-boston-history/GyR05Y6VYfzL4mqPJranSO/story.html

http://fortune.com/2017/01/23/womens-march-signs-museums-history/

https://www.newberry.org/node/6870